A,b,c,d, Meet My Family Rhyme and Chant Poster

The types of texts that children employ and create aggrandize and abound in complexity as they develop.

Overview

Children engage with a range of texts throughout early childhood, including fiction and nonfiction books; likewise magazines, brochures, posters; diverse art forms like poetry, cartoon, painting, and sculpture; as well equally multimedia and information communication technology (ICT) texts.

The types of texts that children create likewise expand and grow in complication every bit they develop, allowing them to employ texts for a variety of personal and social purposes:

[Children] create and display their information in a way that suits dissimilar audiences and purposes. Victorian early years learning and development framework (VEYLDF) 2016

This department will explore the utilize of texts for a range of purposes (personal, imaginative, informative), types of children's literature, and multimedia and ICT texts.

This learning focus is about developing children's sensation of how texts work, and how a diverseness of texts tin can be used to communicate.

This learning focus concerns the functions and purposes of texts; that is how they are used (as per the four resources model: Freebody and Luke, 1990). This learning focus differs from making meaning and expressing ideas (emergent literacy), which looks at how children engage in making meaning from texts and create meaning within their texts.

The importance of exploring and creating texts

Children's evolution of literacy skills is supported past frequent, and rich experiences with print and texts. The Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF, 2016) highlights that children "appoint with a range of texts and get meaning from these texts" (Outcome 5.2).

This includes exploring and agreement texts written past others (linking to emergent reading comprehension). It also includes children creating their texts, to record, reflect, entertain, inform, instruct, and even persuade others (linking to emergent written expression).

This exploration and creation of texts not only enables children to express themselves through a range of media just likewise paves the way for children's later literacy success (come across MacKenzie and Veresov, 2013).

The VEYLDF (2016) also emphasises that children "begin to empathize how symbols and design systems piece of work" (Result 5.four) and "utilize information and communication technologies to access information, investigate ideas and correspond their thinking" (Outcome 5.5). In this way, developing children's competence in exploring and creating a multifariousness of texts prepares them for the opportunities and challenges of the 21st Century (see Saracho, 2017a, for discussion).

Using texts for a range of purposes

Texts are created to achieve certain purposes (for example writing a letter, telling a story, sharing data).

There are many more kinds of texts that can be covered in detail in this toolkit. The post-obit three types (genres) are age-advisable for early babyhood settings, and take been adapted from Fellowes and Oakley (2014):

- personal (expressive) texts, including letters, diaries, journals, and notes

- imaginative (narratives) texts, including stories, fairytales, poems, and play scripts

- informative (expository) texts, including reports, explanations, procedures, and persuasive writing.

Different types of texts accept specific features including:

- the topic and content

- the mode information is organised (text construction)

- types of sentences used (for example present or past tense)

- various vocabulary.

While certain types of texts will take specific features that children will get familiar with, Fellowes and Oakley (2014, p. 379) remind educators that:

Text composition rarely completely conforms to a single model standard. Communicative purposes are achieved using more interesting and dynamic texts when compositional flexibility is practical….

Over time and with the right experiences, children volition probable develop a more innate ability to apply structure to the texts they write, and a more sophisticated and flexible control of the organisational and language requirements.

Personal (expressive) texts

Personal (expressive) texts refer to various forms of writing, used for recording, sharing, or describing personal experiences, events, or ideas.

The kinds of personal texts that children would encounter in everyday life include:

- letters, cards, and messages from family and friends

- digital letters, emails, posts, and other communications sent via online media.

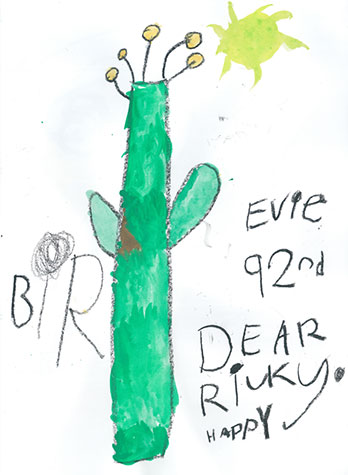

These are likely to be multimodal: they may take visual (pictures and images), audiovisual (voice, music, video), as well equally written words. They volition also have features specific to the personal text type, for example, a letter starting with Dear [Proper noun].

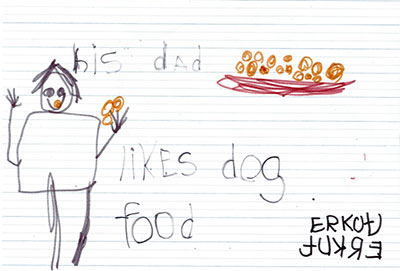

Creating personal texts is a useful opportunity for developing emergent literacy during writing with children. Examples of personal texts that children create include marking makings, drawings, writings (and annotations by adults) for:

- recounting an event

- expressing feelings or reactions

- sending a message to family and friends.

Children tin can brainstorm to write personal (expressive) texts when they start using cartoon, writing materials, or digital media. Through intentional learning experiences, children can learn to construct texts relating to their personal experiences (for instance a visit to the zoo), people they know (my family, my friends), or past/upcoming events (incursions/excursions).

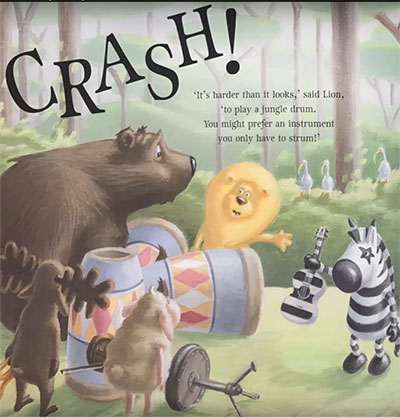

Imaginative (narrative) texts

The two main types of imaginative texts are narratives (stories) and poems. Both are forms of text that come from the author'southward imagination.

Narratives

Stories are a medium with which all children can become familiar and relish. Narratives can exist oral or written. They can also be presented through art and theatre, or through audio-visual media like film, television, sound and music.

Every story has at to the lowest degree a start, middle, and end.

Start

- once, a male child called Jack traded his cow for some magic beans.

Middle

- from the beans sprung a huge beanstalk, which atomic number 82 Jack to a giant's castle in the heaven.

End

- when Jack tried to steal the treasures, the giant chased him downwardly the stem. Jack cut the stalk, and the giant brutal.

All narrative texts accept the elements of setting, character, plot, and themes or messages within the story. Almost stories will have a consummate "episode" (Story Grammar: Stein and Glenn, 1975).

See the Stories and Narratives learning focus page for more information.

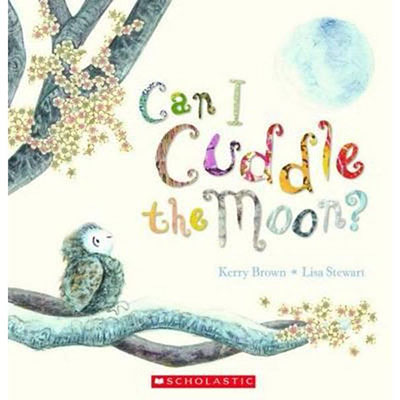

Children's exposure to narrative texts is mainly through moving-picture show storybooks. However, other narrative text forms include art, pattern and theatre, or multimedia texts similar film, boob tube, audio and music.

See further below for examples of children's literature.

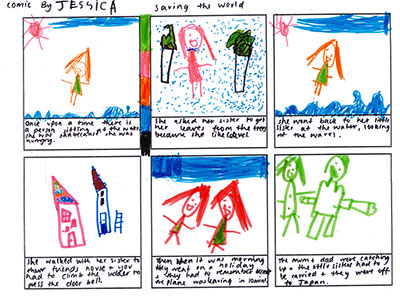

Through writing experiences, children's learning can exist scaffolded to create their narrative texts. It may be a claiming to determine when children's writing (including mark makings, drawings, written messages and words -and annotations by adults), counts every bit a 'story'. However, it is important to care for children's drawing and writing as communicative and to encourage children to explain or express what their piece of work means, through exact or nonverbal advice.

Some examples of narrative texts that children may begin to describe and write in early childhood include:

- mark marking and scribbling

- drawings and paintings (with or without annotations)

- comic strips

- digital drawings/paintings

- photos, videos, sound recordings, and mayhap a combination of these

- early written stories with approximations of letters and symbols, and images

- images accompanied by a few sentences as part of a written story.

with educator annotations. Image: University of Melbourne Early Learning Centre.

Poesy

Poetry is a form of writing that helps readers to hear, encounter, and experience what is being described. Common forms of poetry include limericks, acrostics, ballads, haikus and couplets. Poems oftentimes include language elements such as:

- repetition of words, phrases, and sentences

- rhyme

- alliteration (for case ten tiny toys)

- onomatopoeia (where a word's sounds mimic the audio being described, for example, ding, fizz, thud)

- imagery, metaphor, simile (see higher-order linguistic communication).

Higher-lodge language

Poetry and rhyme are often used in children's literature and music. See these verses from A House for Donfinkle past Choechoe Brereton:

Up high in the grasslands

where Wooble Beasts roam,

Donfinkle Vonkrinkle

is edifice his home.

The mud walls are perfect,

the door just divine,

the Windows are beech wood,

the porch is all pine.

When scaffolded past educators, children can savour engaging with poetic texts and start to get enlightened of language elements like rhyme, alliteration, and repetition.

Educators may also facilitate co-writing of poetry with children using bones forms of poetry like haiku.

The post-obit examples come from a four-year-old kindergarten room at the University of Melbourne Early on Learning Centre.

They were composed by children, in collaboration with their educators/teachers who helped scaffold their expression, and scribe their ideas downwards:

A flower and a snail

Talk and listen.

They are friends.

Bluegum nuts-

They have reflection

Of the sky on them.

Examples of children'southward haiku. Four-year-former kindergarten room at the University of Melbourne Early Learning Middle.

An instance of a rhyming poem equanimous past a iv-year-onetime:

I am falling into the water

And my seagull is falling with me.

Nosotros are falling into the sea.

At that place are flowers in the ocean.

Examples of kid'due south rhyming poem. Four-year-old kindergarten room at the University of Melbourne Early on Learning Centre.

Here are some other examples of poems by children who had been composing in collaboration with their educators/teachers beyond the Kindergarten twelvemonth:

Butterflies expect unlike

on a jump day.

They hide within their wings.

When I run into logged forest

my center breaks

similar glass.

The Sun is playing

with a ball

on a soft cloud.

Examples of children'southward haiku. Iv-twelvemonth-old kindergarten room at the University of Melbourne Early Learning Centre.

Her long dirty apparel

Her long dingy dress is dotted

with sunny wattles.

her pockets are filled

with gumnuts, feathers and leaves;

She is a firm

for noisy birds,

pink dolphins of the past;

She flows from the mountains

of shadows and mist

to a bay that's not too far;

Oooo, who is she?

Birrarung Marr

Who is she?

Birrarung Marr.

Examples of group poems, composed during grouping fourth dimension. Four-twelvemonth-one-time kindergarten room at the University of Melbourne Early Learning Middle.

The higher up examples demonstrate how children can exist facilitated in their expression, through collaborative writing experiences that slowly build from simple to more circuitous poems.

Notation: Children composed poems orally and educators/teachers scribed their ideas. Later on, some children started to write (some of) their poems in their handwriting with support.

Informative (expository) texts

Texts that explain, talk over, or provide information are frequently called informative (or expository texts). These texts can apply a combination of written, visual, and auditory information to convey letters. Three main types of expository texts are informative, procedural, and persuasive texts.

Informative texts

Informative texts include descriptions, explanations, reports, discussions, and lists. The purpose of this kind of communication is to provide information about a particular topic.

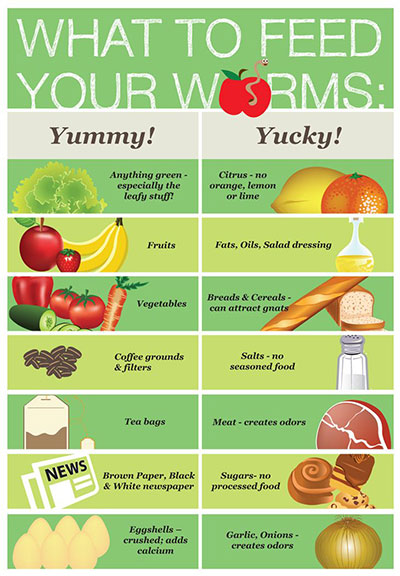

Informative texts can include several features including a clear topic or theme, descriptions and details near the topic, and a decision summarising data in the text. Informative texts tin can besides include visuals - diagrams, graphs, charts, pictures, and maps. If they are a digital informative text, like a webpage or app, they may also include audio and video.

Some examples of functional informative texts for children to appoint with and write, in collaboration with educators, have been suggested past Fellowes and Oakley (2014 p. 377), including:

- preparing for an excursion past writing a reminder list of the things to be taken

- talking and and then drawing/writing almost favourite animals or places and assembling them to make a book

- drawing/writing labels for material containers and special areas of the room so they tin can be easily located.

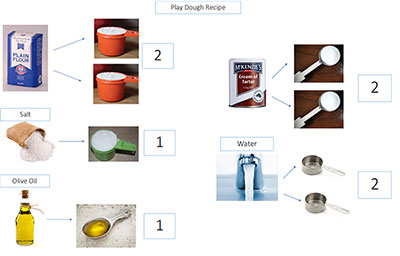

Procedural texts

The purpose of procedural texts is to provide instructions in a logical sequence to achieve a goal. Common examples of instructions/procedures that children can explore and create include:

- recipes

- connective blocks instructions (for example Duplo® or Lego®)

- instructions for games (for example how to play Simon Says)

- treasure hunt instructions/maps.

When given a set of instructions, these components are unremarkably included:

- an introduction with an overview of the goal/product

- a list of materials/items needed to complete the job (for instance ingredients, resources, parts)

- and a sequence of directions that provide step-by-stride details.

Instructions/procedures oft include visual, written (and sometimes audio-visual) information.

Downloadable Visual Recipe

Persuasive texts

Persuasive texts are designed to convince someone of an idea or stance. In written form, these texts are not ofttimes encountered in early childhood settings only may be introduced in functional ways that support children's specific strengths and capabilities, including:

- posters showing why people should respect and intendance for 1 another

- a affiche or sign providing reasons to recycle

- a song or video talking about why art is fun

- writing a sign to go over a fish tank advising people virtually required behaviour when feeding the fish, or cleaning their tank.

Persuasive texts have the post-obit main features:

- a central idea of which the reader/audience is being convinced

- key reasons/arguments to support the thought

- examples or evidence that demonstrate why the arguments are true.

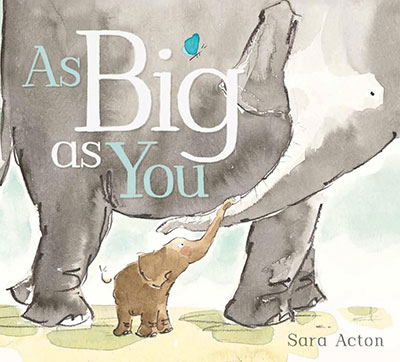

Children'due south literature

In this section, an overview of types of children's literature will be explored. Note: These categories cross over significantly! Some books are in multiple categories and can be used for multiple purposes.

Note that educators play a significant role in creating intentional learning experiences with texts (see the education exercise, reading with children).

Some broad categories of texts include:

Motion-picture show storybooks

- include diverse kinds of stories (narratives), nursery rhymes

- tin can be fictional, or stories based on real-life (factual)

- Australian and international books

- themes and concepts from multiple cultures and times.

Non-fiction or concept books

- introduce new vocabulary, concepts and knowledge

- engagingly provide information, to develop children's concept noesis and vocabulary

- for instance Dig Dig Excavation past Margaret Mayo

- for example Rumble in the Jungle by Giles Andreae

Rhyming or songbooks

- books based on a song or rhyme

- permit children to acquire the words of the volume and chant or sing forth

- develops phonological awareness and vocabulary

Wordless books

- books with a series of pictures that show the narrative

- allow adults or children to narrate the story

- for example The Snowman by Raymond Briggs

- for example The Blood-red Volume by Barbara Lehman

Interactive books

- popular-up, lift-the-flap, foldouts, affect and feel books

- activity books such as pasting, gluing, colouring, and talking books

- interactive opportunities encouraging children to interact with books, and develop fine motor skills

- for example Dearest Zoo and the Spot volume series by Eric Loma

- for instance Snip Snap Popular Up Fun by Jonathan Litton

Anticipated books

- repetition and reinforcement encourage children intrinsically

- let for opportunities to predict what will happen, or what word will be next

- children can use these books for independent reading and start to tell the story in their own words

- for case Brown deport, Brown bear, What So You Run across? by Beak Martin, Jr.

- for instance Hattie and the Fox by Mem Trick

Alphabet, counting and word books

- provide models of letters, numbers and words in uncomplicated and bright books

- children can frequently begin to place letters, numbers and words using these books.

Sturdy lath, textile or plastic books

- well-constructed, sturdy books, for children to handle at any age, but specially easier to hold and manipulate for infants and toddlers

- give children the opportunity to handle books without worrying near ripping pages.

Real-life themes and multi/cross-cultural books

- deal with real-life issues in a sensitive and accurate manner

- provide opportunities to develop empathy and discuss feelings

- for example family bug, new babies, moving business firm

- for example books about other cultures, lifestyles, and individual differences

- encourage sensation and appreciation of diversity

- for instance, The When I'chiliad Feeling … series by Trace Moroney

- for case Kangaroos Hop past Ros Moriarty.

Bilingual or multilingual books

- provide text in English and other languages, including several Aboriginal languages

- promote diversity, inclusivity and encourage agreement of other cultures, traditions and histories

- audio-visual combinations of books with CDs or DVDs, which provide additional ways for children to experience and engage with multilingual literature

Others

- reference books (Illustrated dictionaries, thesaurus, encyclopaedia)

- paperback books for young children

- magazines (and other information texts like brochures, flyers, posters)

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) texts

- opportunities for children to compare dissimilar media, even at a very young age

- encounter examples below

Multimedia and ICT texts

Multimedia or ICT texts refer to the dissimilar texts and media that children may appoint with including internet sites, apps and programs, film, videos, music, audio, photographs – and many others! These texts are frequently:

- multimodal (integrating images, written words and/or audio), and

- interactive (responsive to touch, voice, typing, or other inputs).

It is essential for educators to exist enlightened of ways to use multimedia and ICT texts strategically for intentional teaching, as the VEYLDF (2016) notes that children "utilize digital technologies and multimedia resource to communicate, play and learn".

Many children come up to early childhood settings with an sensation of ICT tools including smartphones, tablets, computers and digital toys. Through engagement with this digital technology in the abode, children may develop a range of digital skills exterior of early on childhood settings.

Some benefits of multimedia and ICT texts include, that they:

- are an engaging and interactive medium

- provide children with multimodal learning

- provide access to data from global and various sources

- allow children to develop their digital literacy skills

By using technology purposively and strategically with children, educators can heighten play and learn in traditional contexts.

Strategies for exploring and creating multimedia and ICT texts

These are some suggested strategies to make the best use of multimedia and ICT texts in early babyhood settings:

- ensure intentional use for a specific learning purpose

- embed language modelling and concept evolution within ICT experiences

- allow time for purposeful play and exploration

- apply digital engineering science to allow for equity of opportunity

- when technical difficulties arise, use these as learning experiences, to scaffold children's apply of digital engineering

- be aware of child condom and use of approved digital applied science policies

- create clear guidelines for use of digital tools

- ensure acceptable supervision of children using digital engineering science

- plan experiences to build upon children'south previous successes with digital technology

Adjusted from Alper (2013) and Lim (2012).

Theory to do

In line with the Four Resource Model (Freebody &Luke, 1990), exploring and creating texts is nearly children learning how to use texts (for case becoming Text Users).

By engaging with a range of different text types (genres), children acquire nearly how texts work, their master features, and how to use them for a variety of social (and eventually academic) purposes.

The Text User knows about the dissimilar functions of texts, and their features —the style texts are structured, their sequence of components, and the kinds of language used inside them. For example, children acquire the differences between personal, imaginative, and informative texts. They also recognise like texts past their features and arrangement.

In improver, for children soon to transition to school, they may start to analyse texts, as a grade of emergent critical literacy in collaboration with educators. This could include scaffolding children's thinking by request them what they liked about sure texts, and why they did/did not like a text. In Freebody and Luke'southward (1990) model, this is referred to as the Text Analyst.

Evidence base

Past engaging purposively with a range of books and resources, children are existence prepared for the various texts they will encounter in one case they transition to primary school. These engagement opportunities include:

- learning how texts work

- making meaning from texts they engage with

- creating their texts (in visual, written, or multimedia grade).

Research reviews bear witness that educators should cull both narrative and information texts to explore with children, but that they demand to:

(a) be visually stimulating and aesthetically pleasing to motivate children to interact with the books, (b) encourage children to re-read them several times, (c) be of involvement to … children, (d) exist familiar to the children, and (e) reflect their home surroundings and daily lives.

- Saracho (2017b, p. 561)

Evidence shows that making significant from and writing narrative texts is an important skill for early reading and writing success (Saracho, 2017b).

In addition, growing research shows the benefits of advisory (non-fiction) texts in early on childhood. Price, Bradley and Smith (2012) found that educators engaged in more agile word about informational texts, than when reading storybooks.

Other enquiry has shown that when children explore information text by themselves, they are more likely to mimic the language used by adults during reading aloud, than with storybooks (Massey, 2014).

Other show shows the importance of illustrations for facilitating children'south pregnant-making and remember of stories (Greenhoot, Beyer and Curtis, 2014); and new show suggests that using wordless picture books can advance the quality and quantity of children'south language production during shared reading experiences (Chaparro-Moreno et al., 2017).

Finally, while more enquiry is needed to make up one's mind whatever potential limitations with digital texts over paper-based texts, digital storybooks appear to provide benefits in children'south date with texts (Bus, Takacs, Kegel, 2015).

Links to VEYLDF

Victorian early years learning and development framework (VEYLDF, 2016)

Event 2: community

Children become aware of fairness

- begin to understand and evaluate ways in which texts construct identities and create stereotypes.

Consequence 5: communication

Children engage with a range of texts and get meaning from these texts

- listen and respond to sounds and patterns in speech, stories and rhymes in context

- view and heed to printed, visual and multimedia texts and respond with relevant gestures, actions, comments and/or questions

- begin to understand fundamental literacy and numeracy concepts and processes, such equally the sounds of linguistic communication, alphabetic character-sound relationships, concepts of print and the ways that texts are structured

- explore texts from a range of different perspectives and begin to analyse the meanings

- actively use, engage with and share the enjoyment of language and texts in a range of ways

- recognise and appoint with written and oral culturally constructed texts

Children express ideas and make meaning using a range of media

- share the stories and symbols of their own cultures and re-enact well-known stories

Children begin to understand how symbols and pattern systems piece of work

- develop an understanding that symbols are a powerful means of advice and that ideas, thoughts and concepts tin be represented through them

- brainstorm to be aware of the relationships between oral, written and visual representations

- brainstorm to recognise patterns and relationships and the connections between them

- begin to sort, categorise, society and compare collections and events and attributes of objects and materials in their social and natural worlds

- listen and respond to sounds and patterns in speech, stories and rhyme

- draw on the retentivity of a sequence to consummate a task

- draw on their experiences in constructing pregnant using symbols.

Children use information and communication technologies to access data, investigate ideas and represent their thinking

- use data and communication technologies to admission images and information, explore diverse perspectives and make sense of their earth

- use information and communications technologies as tools for designing, drawing, editing, reflecting and composing

- engage with engineering for fun and to brand meaning

Experiences plans and videos

Early on communicators (nascency - 18 months)

- Worm farm: discussion effectually texts

Early language users (12 - 36 months)

- Drawing as writing

- Worm subcontract: discussion around texts

- Stories to tell

For linguistic communication and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months)

- Posting with friends

- Watching sprouts abound

- Megawombat drawing telling

- Making comics: creating visual narratives

- Stories to tell

Learning foci and teaching practices

- Fine arts

- Higher-guild language

- Independent reading and writing

- Stories and narratives

- Literacy-rich environment

- Performing arts

- Play

- Reading with children (Emergent literacy)

- Sociodramatic play

- Writing with children

References

Alper, M. (2013). Developmentally appropriate new media literacies: Supporting cultural competencies and social skills in early childhood educational activity. Journal of Early Babyhood Literacy, 13(ii), 175-196.

Bus, A. G., Takacs, Z. K., and Kegel, C. A. T. (2015). Affordances and limitations of electronic storybooks for young children's emergent literacy. Developmental Review, 35, 79–97.

Chaparro-Moreno, L. J., Reali, F., and Maldonado-Carreño, C. (2017). Wordless moving picture books heave preschoolers' language production during shared reading. Early Childhood Inquiry Quarterly, 40, 52–62.

Fellowes, J., and Oakley, Grand. (2014). Language, literacy and early childhood education, 2nd Edition. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Printing.

Freebody, P.,& Luke, A. (1990). Literacies programs: Debates and demands in cultural context. Prospect: An Australian Journal of TESOL,5(3), 7-xvi.

Greenhoot, A. F., Beyer, A. M., and Curtis, J. (2014). More than pretty pictures? How illustrations affect parent-kid story reading and children's story remember. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–10.

Lim, E. (2012). Patterns of kindergarten children'due south social interaction with peers in the computer area. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, vii(3), 399-421.

MacKenzie, N., and Veresov, N. (2013). How drawing can support writing acquisition: Text construction in early on writing from a Vygotskian perspective. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(4), 22-30.

Massey, Southward. Fifty. (2014). Making the case for using informational text in preschool classrooms. Creative Instruction, 5, 396–401.

Pappas, C. C. (2006). The information book genre: Its office in integrated science literacy research and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 41(2), 226–250.

Cost, L. H., Bradley, B. A., and Smith, J. M. (2012). A comparison of preschool teachers' talk during storybook and information book read-aloud. Early Babyhood Research Quarterly, 27(3), 426–440.

Saracho, O. Due north. (2017a). Literacy and linguistic communication: new developments in research, theory, and do. Early Child Development and Care, 187(three–four), 299–304.

Saracho, O. N. (2017b). Parents' shared storybook reading–learning to read. Early Child Development and Care, 187(iii–iv), 554–567.

Stein, N. L., and Glenn, C. G. (1975). An analysis of story comprehension in elementary school children: A test of a schema. In R. O. Freedle (Ed.), New Directions in Discourse Processing (pp. 53–120). Norwood, NJ, US: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Victorian Land Authorities Department of Education and Grooming (2016) Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (2016). Retrieved 3 March 2018

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Dominance (2016). Illustrative Maps from the VEYLDF to the Victorian Curriculum F-10. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

Zevenbergen, R. , and Logan, H. (2008). Figurer use by preschool children: rethinking do every bit digital natives come up to preschool. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 33(1), 37-44.

Additional resource

- Premier's Reading Challenge

- The Children'due south Volume Council of Australia

- 30 Books to Read Before You're Iii

Source: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/childhood/professionals/learning/ecliteracy/emergentliteracy/Pages/exploringandcreatingtexts.aspx

0 Response to "A,b,c,d, Meet My Family Rhyme and Chant Poster"

Enviar um comentário